12.4 Etiology and mechanism of mitral regurgitation

Many conditions may lead to valvular incompetence. Mitral regurgitation is classified as a structural or functional phenomenon. In the former the valve or subvalvular apparatus demonstrates some type of morphological abnormality while functional mitral regurgitation is a consequence of ventricular remodeling. Remember that the left ventricle is closely linked to the function of the mitral valve. Irregular geometry of the ventricle influences the shape, position and function of the annulus, the subvalvular apparatus, and the leaflets. Importantly, a functional component of regurgitation may also be present in structural mitral regurgitation.

Structural mitral regurgitation is also known as organic or primary regurgitation.12.4.1 Structural mitral regurgitation

The mitral valve and its function may be affected by various diseases and conditions. These include aging, mitral valve prolapse, rheumatic heart disease, endocarditis, or congenital abnormalities. Drugs may also damage the valve and thus cause regurgitation. Transthoracic echocardiography may be used to clarify the cause of regurgitation. All of the above mentioned entities will be covered in the following sections. Regurgitation in the setting of artificial valves will be discussed in the chapter on prosthetic heart valves.

12.4.1.1 Aging of the mitral valve

As mentioned earlier, mitral regurgitation is a common phenomenon. You will find trivial or mild forms even in young individuals with no apparent structural abnormalities. However, the prevalence of mitral regurgitation increases with age. This is usually the result of sclerosis, fibrosis and calcification of the valve, chords, and the papillary muscle (papillary muscle fibrosis). The thickness of the valve increases with age. The leaflets and the subvavlular apparatus "shrink" and become less pliable. Another common finding is annular calcification. The ring of the mitral valve becomes stiffer and impairs the normal physiology of the mitral valve. Several factors may accelerate aging of the mitral valve, and especially mitral annular calcification. These include hypercalcemia, hypertension, renal insufficiency, atherosclerosis, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, smoking, and rheumatic heart disease. Ethnic origin plays a role in this condition. Such abnormalities, although rare, cause significant degrees of regurgitation. They may contribute to the severity and function of mitral regurgitation in the presence of other mitral valve pathologies. On the echocardiogram, sclerosis, fibrosis and calcifications appear as areas with increased echogenicity. The entire valve may look "brighter". Occasionally one finds small dense areas on the leaflets. Calcifications and regions with heavy fibrosis will also demonstrate "shadowing" distal to the lesion.

Annular calcification at the posterior ring Papillary muscle fibrosis Color Doppler in a patient with degenerative MR Annular calcification is most frequently found in the "posterior" aspect. It may impair the closing motion of the posterior leaflet.12.4.1.2 Mitral valve prolapse

In mitral valve prolapse the valve protrudes beyond the mitral annular plane into the left atrium. Prolapse may affect portions of a leaflet (i.e. scallop), only one leaflet, or the entire valve. The term "mitral valve prolapse" in the strict sense is a functional definition. It may occur in the presence of various diseases such as endocarditis, "fibroelastic deficiency", and even rheumatic heart disease. It may also occur when the annulus is small or squeezed - as in the presence of excessive right heart dilatation.

"Secondary" mitral valve prolapse in a patient with right-ventricular dilatation and a pericardial effusion. Squeezing of the annulus leads to prolapse. Secondary prolapse does not cause severe regurgitation.When we refer to mitral valve prolapse we usually mean a specific pathology of the mitral valve, referred to as degenerative myxomatous mitral valve prolapse, and also known as Barlow's disease, floppy mitral valve, or classic mitral valve prolapse. Myxomatous mitral valve prolapse is characterized by an abnormal tissue composition with mucopolysaccharide accumulation, and changes in collagen and elastic fibers. This leads to functional impairment and affects the competence of the valve. In addition, it weakens the tissue and may lead to chordal rupture (see section on flail leaflet).

Myxomatous mitral valve prolapse on a parasternal long-axis view: Note the thickened leaflets and chordae.

Myxomatous mitral valve prolapse (bi-leaflet) on a four-chamber view Mitral valve prolapse is the most common cause of chordal rupture. The degree of mitral regurgitation in mitral valve prolapse depends on many factors, such as the symmetry of the valve, and is not strictly related to the degree of morphologic abnormalities.Myxomatous mitral valve prolapse is a progressive disease with a hereditary component (autosomal dominant). Approximately 30-50% of first-degree relatives also have mitral valve prolapse. It is often diagnosed in young adults, more commonly in women, and is frequently associated with tricuspid valve prolapse (40-50%). The aortic valve is involved in 10-20%. There is also an association between mitral valve prolapse and skeletal abnormalities of the chest.

Mitral valve prolapse is frequently present in the Marfan syndrome.It should be noted that prolapse is just one morphological component of this disease. Other findings include thickened leaflets and chordae, excessive tissue, and rocking motion of the annulus. Thus, the diagnosis of myxomatous mitral valve prolapse should not only be based on the presence of a prolapse but also on other findings. Mitral valve prolapse may affect the entire valve, only one leaflet, or specific segments or scallops. The echocardiographic investigation should encompass the entire valve. Basically all views that demonstrate the mitral valve permit the diagnosis. However, because the mitral valve is saddle-shaped, it may apparently demonstrate a prolapse on the four-chamber view.

Mitral valve prolapse with moderately thickened valve and rocking motion of the annulus. In mitral valve prolapse you should fully describe: a) the morphology of the valve (thickening), b) the extent and location of prolapse, c) the degree, mechanism and origin of mitral regurgitation, and d) coexistence of chordal rupture. Myxomatous mitral valve (floppy valve, Barlow's disease) Prevalence = 2-3 % Rapid multiplication of cells Rocking motion of the annulus Involvement of the entire subvalvular apparatus Billowing Excessive tissue Segmental involvement Thickened chordae- Prevalence = 2-3 %

- Rapid multiplication of cells

- Rocking motion of the annulus

- Involvement of the entire subvalvular apparatus

- Billowing

- Excessive tissue

- Segmental involvement

- Thickened chordae

12.4.1.3 Rheumatic heart disease and mitral regurgitation

Although the primary finding in rheumatic heart disease is stenosis, many patients will also have regurgitation. In some patients regurgitation may become the predominant condition. The diagnosis of "rheumatic mitral regurgitation" is based on the presence of mitral valve doming and other typical features of rheumatic heart disease. The mechanism of regurgitation may vary, but the cause is usually leaflet restriction related to chordal shortening and retraction of the leaflets. Secondary degeneration also contributes to incompetence. Thus, regurgitation is more common in elderly patients with rheumatic heart disease. Rheumatic valve disease also predisposes an individual to endocarditis, which leads to destruction and incompetence of the valve. Patients who have undergone valvuloplasty almost always experience regurgitation, which tends to worsen after the procedure. Here the origin of the regurgitant jet is usually located in the region of the commissures - the site where the valve tears during the procedure.

A myxomatous mitral valve and rheumatic heart disease may exist together Rheumatic MR: Two-dimensional image showing doming of the anterior leaflet. Note the posteriorly directed jet and aortic regurgitation.12.4.1.4 Endocarditis and mitral regurgitation

Valvular incompetence is a common consequence of endocarditis. It may lead to acute life-threatening mitral regurgitation, but may also result in less severe forms and become chronic. The spectrum of valvular abnormalities caused by endocarditis is wide; it includes chordal rupture (flail leaflet), leaflet perforation, ruptured psuedoaneurysms, leaflet restriction, and complex mechanisms such as annular abscess cavities or valvular dehiscence. The condition is easily diagnosed in the acute setting of endocarditis, based on the presence of vegetations and other typical diagnostic features of endocarditis. However, once the endocarditis has "healed", things become more difficult. One may find residues of the infection, such as regions of increased echogenicity (calcifications and fibrosis) or chordal rupture. More on endocarditis and its sequelae can be found in Chapter 15 (Endocarditis).

Mitral valve endocarditis with vegetation on the mitral valve

Endocarditis leading to mitral regurgitation12.4.1.5 Drugs and mitral regurgitation

Reports of valvuloplasty caused by phentermine and fenfluramine (drugs which were prescribed for obesity), reported in 1990 by Connolly et al., attracted renewed attention to this condition. However, these drugs are by far not the only substances that affect heart valves. Methysergide, an ergot alkaloid used for the treatment of migraine, has been known to affect heart valves from the mid nineteen sixties. Meanwhile there are several substances, many of which are based on a serotininegic pathway and have similar effects. These include pergolide and cabergoline (for the treatment of Parkinson´s disease) and recreational drugs such as ecstasy. Most of these drugs are now banned from the market or approved for very specific indications.

It is not entirely clear how these substances interact with valve tissue. They have been shown to enhance serotoninergic activity, which ultimately leads to subendocardial fibrosis. Echocardiography enables the clinician to detect retraction and shrinkage of the valve. As the valves commonly do not show any peculiar features, the differential diagnosis of functional regurgitation is difficult to establish and is usually based on a "history of drug use".

Drugs associated with MR Pergolide and cabergoline Parkinson MDMA (ecstasy) Psychoactive drug Ergot alkaloids - Migraine headaches Ergot-derived dopamine agonists Parkinson Transesophageal study of a patient with drug-associated mitral regurgitation. Note the coaptation defect.12.4.1.6 Chordal rupture and flail leaflet

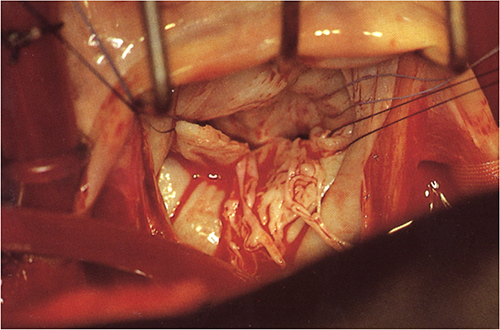

Chordal rupture results in a flail leaflet or - more commonly - in a "partial" flail leaflet. It is most commonly observed in myxomatous mitral valve prolapse and is a result of structural abnormality of the valve. However, chordal rupture may also occur in endocarditis, rheumatic heart disease, elderly patients with degenerative abnormalities of the valve, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and after interventional procedures (i.e. balloon valvuloplasty). Chordal rupture and papillary muscle rupture are different entities. While chordal rupture usually affects just a part of the valve, papillary muscle rupture involves an entire leaflet and thus always results in acute severe regurgitation. As papillary muscle rupture is a potential complication of acute myocardial infarction, this pathology will be discussed in the chapter on coronary artery disease (Chapter 8).

Flail posterior leaflet; note the chordal structures protruding into the left atrium, marked by a fibrillating motion. Discrete form of a flail posterior leaflet

The degree of mitral regurgitation caused by chordal rupture depends on where and what type of chords are involved. When only redundant or supportive chords are ruptured, the patient may have mild or no regurgitation. However, in most cases regurgitation will be significant and will lead to rapid progression of mitral regurgitation.

Chordal rupture most frequently involves the posterior leaflet, especially the middle scallop (P2). The morphology of flail leaflets may vary. Typical findings in echocardiography are summarized in the following table.

Detached chordal structures protruding from the flail leaflet into the left atrium Concave position of the leaflet towards the left atrium Eccentric direction of jet Rapid flutter motion of the ruptured leaflet tip or chord Parallel position (contour) of the flail, and the opposing leaflet Prominent flail posterior leaflet on an apical 3-chamber view with and without color Flail posterior leaflet with “saloon door" effectTo detect a flail leaflet, it is important to visualize all segments of the mitral valve including the commissural regions. Use color in combination with 2D echo to pinpoint the exact location of the defect and use high frame rates to display the motion of the flail segments.

Apply the zoom and "RES" function to display a flail leaflet.Small partial flail leaflets may be difficult to identify. It may be necessary to perform a transesophageal study to demonstrate the pathology. Three-dimensional echocardiography is also able to detect a flail leaflet. The ability to display the exact location of the defect on the "en face" view from the left atrium is one of the major advantages of this technique.

Despite the excellent sensitivity of echocardiography, it is sometimes difficult to differentiate vegetations from flail portions of a valve. This is especially true of myxomatous mitral valve prolapse, in the presence of which the leaflets are thickened.

Both, vegetations (endocarditis) and a flail leaflet may be present in a patient. One should bear in mind the fact that the flail leaflet may have been caused by endocarditis. Patient with vegetation on the anterior leaflet, mimicking a flail leaflet Aging Rheumatic MR Endocarditis Common Doming of AMVL Valve destruction Thickened MV Other rheumatic features Perforation Annular calcification Combined MS + MR Leaflet rupture Differential diagnosis of MR12.4.1.7 Systemic diseases and mitral regurgitation

The mitral valve may be affected by systemic diseases. These include systemic lupus erythematodes (Libman-Sacks endocarditis), Still's disease, endomyocardial fibrosis, and amyloidosis. Usually mitral regurgitation is mild, but a few severe forms have also been reported. A more detailed description will be provided in the corresponding chapters.

Transesophageal study in Libman-Sacks endocarditis; small vegetations are seen on the valve

Mitral regurgitation in Libman-Sacks endocarditis12.4.1.8 Congenital mitral regurgitation

Congenital malformations of the mitral valve are rare. In more than 60% of cases they are associated with other cardiac lesions. The most common abnormality that causes regurgitation is a cleft mitral valve. The latter is always present in patients with a primum atrial septal defect (endocardial cushion defect), but may also exist on its own. With echocardiography the defect is best seen on a short-axis view of the mitral valve. Here you can observe a "discontinuity" of the anterior leaflet with a jet that passes right through the defect (cleft). The spectrum of other abnormalities ranges from a parachute mitral valve, a double orifice mitral valve, to an anomalous papillary muscle rotation.

Parachute mitral valve12.4.2 Functional mitral regurgitation

Mitral regurgitation is classified as functional (or secondary) when the valve is structurally normal. Valvular incompetence is caused either by annular dilatation, leaflet tethering, or distortion of mitral valve geometry. A combination of these mechanisms is also possible.

Functional mitral regurgitation is common in ischemic and dilated cardiomyopathy12.4.2.1 Annular dilatation

Annular dilatation is a consequence of left ventricular enlargement. As there are many conditions in which the left ventricle is dilated, annular dilatation is not specific for a single pathology. It results from the size of the ventricle as well as its shape. Patients with more prominent dilatation of the apex but preserved diameters at the base will not develop mitral regurgitation. In annular dilatation it is the posterior portions of the ring that expand. The anterior ring is "attached" to the intervalvular fibrosa; its expansion is therefore limited. Typically the ring becomes more round and the leaflets are dragged apart. To a certain degree the mitral valve may compensate this phenomenone, because leaflet coaptation is not a line but an area (see section: 12.2.1 Mitral valve leaflets). The degree to which the mitral valve compensates for annular dilatation depends on the magnitude of the initial coaptation surface (length). When the leaflets are restricted or shortened, regurgitation will occur earlier. In the early stages of functional regurgitation a "defect" will first be present in specific regions of the valve. The more the annulus dilates, the larger the regurgitant orifice will become.

Mitral regurgitation begets mitral regurgitationIn isolated annular dilatation, echocardiography will demonstrate closure of the leaflet close to the annular plane and a reduction in coaptation length. These findings are best appreciated on a four- and three-chamber view. Color Doppler will show a jet that is broadest on a two-chamber view because the line of coaptation is seen best on this view. This must also be considered when quantifying mitral regurgitation. One may find not just one but several small jets. These correspond to the sections of the valve in which the leaflets do not touch each other.

Annular dilatation in a patient with cardiomyopathy with and without color Doppler The line of coaptation is no straight line. To visualize the entire coaptation zone on a two-chamber view you have to tilt the transducer back and forth.12.4.2.2 Restrictive physiology of the leaflets

Geometric abnormalities of the ventricle affect the position of the papillary muscles and thus cause tension to the chordae and the mitral valve leaflets. The leaflets are pulled towards the ventricle and their closing motion is restricted. In addition, the coaptation depth (area) is reduced and the tenting area increased. Restriction may be limited to one leaflet or may involve both. The most frequently form of restricted physiology is that of the posterior leaflet in the setting of inferior/posterior myocardial infarction. Distortion of the ventricle caused by the infarct dislocates the posteromedial papillary muscle laterally and caudally (towards the apex).

Restricted physiology of the posterior leaflet may also be seen in rather small inferior /posterior infarcts.As a result, the position of the posterior leaflet during valve closure is farther away from the annular plane than that of the anterior leaflet. The leaflets are in an "inverted-y" position in relation to each other. This is best seen on a three-chamber view, which also displays reduced motion of the posterior leaflet.

The mechanism of mitral regurgitation in the presence of an inferior infarct is very likely to be one of posterior leaflet restriction.Restricted physiology of both leaflets may also be seen in the presence of global left ventricular dilatation. Some patients experience not only annular dilatation, but also apical and lateral displacement of papillary muscles. This leads to a combination of annular dilatation and leaflet restriction.

In the presence of posterior leaflet restriction the valve is able to compensate less for annular dilatation.Leaflet restriction may also be caused by structural abnormalities of the valve and the subvalvular apparatus. In rheumatic heart disease or other inflammatory conditions, the leaflets and chordae may be retracted, shortened, or curled.

Restriction of both leaflets in color and without color12.4.2.3 Distortion of the mitral valve and the annulus

The most common phenomenon leading to distortion of the mitral valve is "systolic anterior motion" (SAM) of the mitral valve, which causes outflow tract obstruction in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Here the anterior leaflet is dragged towards the septum during systole, away from the posterior leaflet, resulting in a defect of coaptation. More on this entity and its relation to the severity and degree of outflow tract obstruction will be discussed in the section on jet direction and the mechanism of MR, and in the chapter on hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (Chapter 6). Surgical procedures and pathologies that affect the anatomic continuity of the anterior mitral leaflet and the aortic root may also cause functional changes in the mitral valve. Other rare causes include tumors and masses that lead to functional impairment of mitral valve closure (i.e. left atrial myxoma) or distortion of the subvalvular or valvular apparatus, which may occur in the presence of inter- or extracardiac masses (i.e. hematoma, abscess, tumors).

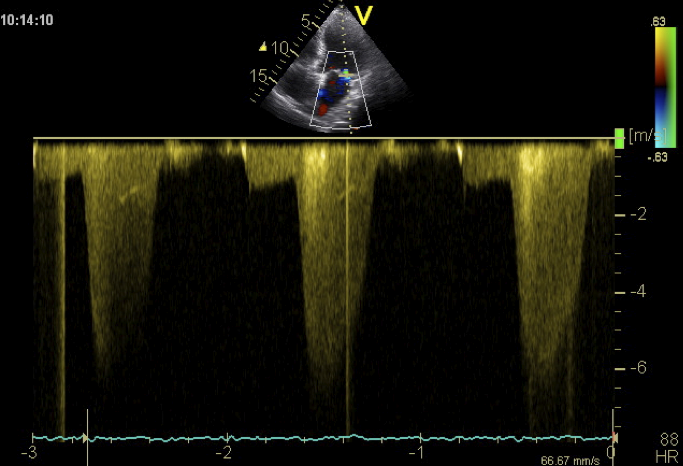

Why is the mechanism important? Etiology Prognosis (reversible) Management (treatment strategy Repair?12.4.2.4 Pre-Systolic mitral regurgitation

Mitral regurgitation is a systolic phenomenon. However, a certain amount of backflow may also occur during diastole. Most commonly this occurs shortly before the onset of contraction (presystolic). Predisposing factors are high left-ventricular end-systolic pressures and the presence of a first degree AV block. This constellation is occasionally observed in patients with dilated or ischemic cardiomyopathy. Left ventricular pressure may exceed left atrial pressure and thus cause pre-systolic mitral regurgitation. Use a CW Doppler spectrum to demonstrate the pre-systolic component of mitral regurgitation. You will see a lower velocity regurgitation spectrum shortly before the QRS complex.