5 ultrasound tips that will make you shine!

How do you become a renowned ultrasound expert? Good imaging skills, an experienced eye, and extensive medical knowledge are not enough. Here are a few important tips that will help you get ahead and make you a true master of ultrasound:

1) Know what you are looking for

Imagine you dropped a bag full of shopping goods. Wouldn’t it be helpful to know what was inside the bag in the first place? The same is true for ultrasound. Of course one should always perform a “complete” exam. But honestly, do we always focus on every little aspect of the heart if we are not searching for something specific?

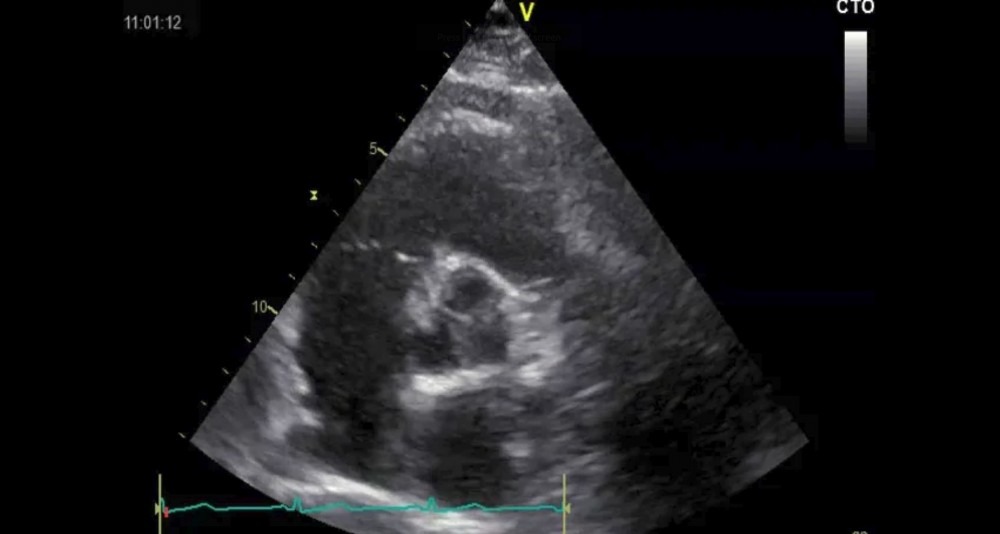

For example: it is easy to miss this small fibroelastoma if you do not know that the patient had a cerebrovascular event:

Fibroelastoma of the aortic valve

Fibroelastoma of the aortic valve

My suggestion is: talk to your patients, get more information from the referring physician, read their charts and look at studies from other imaging modalities.

2) Observe-describe-interpret

We often tend to jump to conclusions too quickly. We see some or a pathology and already think we know what it is. But be careful: the laws of statistics state that even the improbable must occur sometimes.

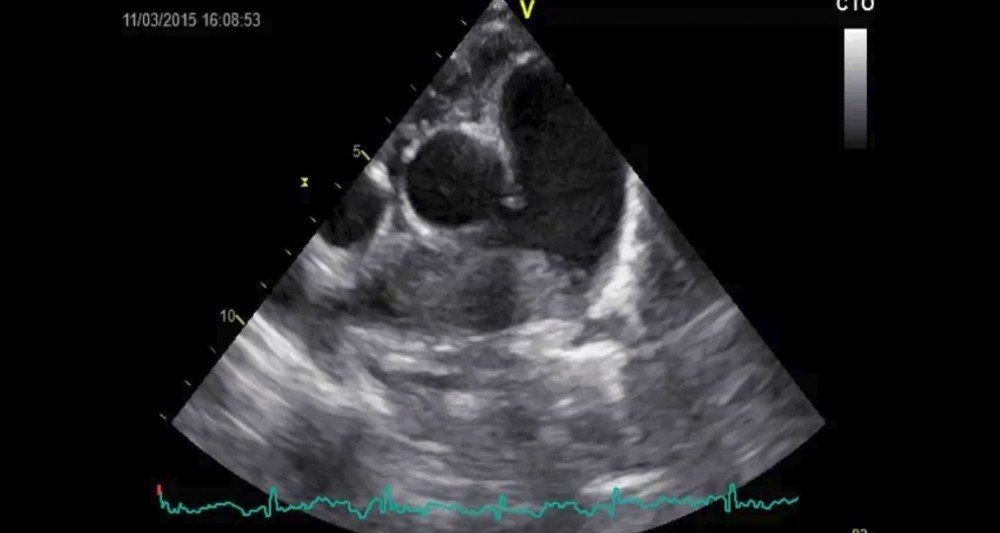

Here is an example: We found a huge mass in the pulmonary artery in a patient with deep vein thrombosis, chronic pulmonary hypertension, and right heart pressure overload.

huge “mass” in the pulmonary artery

huge “mass” in the pulmonary artery

You would probably say this is a thrombus – right? Well not exactly. It turned out to be a rhabdomyosarcoma growing along the pulmonary artery.

My recommendation: observe first – then provide a detailed description (size, location, echogenicity etc.) and finally make your interpretation. But, you should also provide possible other alternative diagnoses. That way you will never be completely off-track.

3) Have the courage to be uncertain

Interpreting sonographic findings is usually not a simple black and white issue. Remember - “eyeballing” plays an important role in ultrasound: “is the texture of the organ normal or is a tumor hidden inside?” “Is mitral regurgitation mild or moderate?” “What about regional wall motion abnormalities?” And most importantly “how is “the” left ventricular function?”

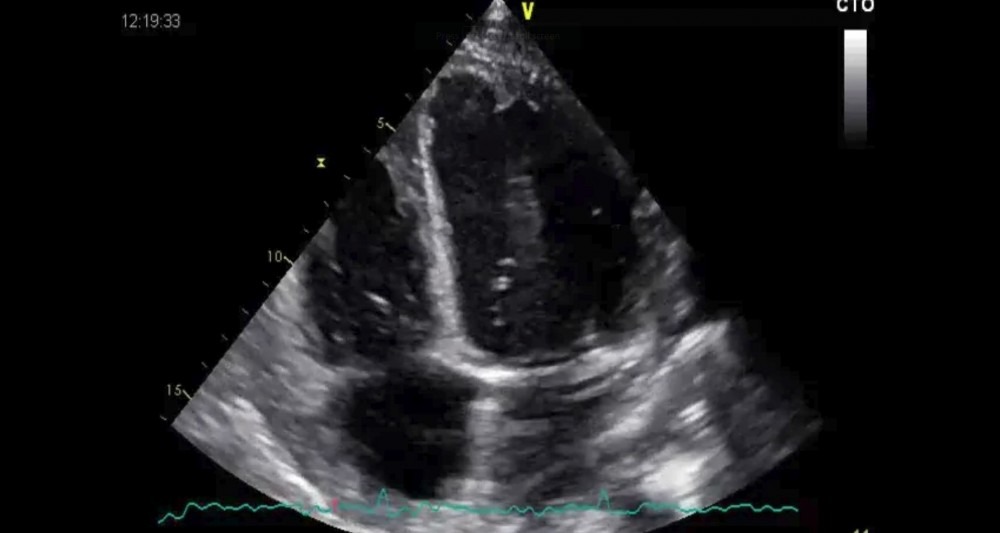

A while ago I posted the following four-chamber view on Facebook and asked our community how they would interpret left ventricular function in this patient.

What is LVF?

What is LVF?

The comments ranged from normal to severely reduced. What is my take? To be honest, I am not sure either. I would say it is probably in the range of moderately reduced. The ventricle has this strange abnormal motion, which makes assessment difficult. That is exactly what I would state in the report. It would read the following: “Difficult interpretation of LVF due to abnormal septal motion - probably moderately reduced LVF.

Don’t be afraid of words such as “probably”, “could be”, “might be”, “unclear” or “it appears”. I think that such terms are important since they state a level of uncertainty. Eventually, they may build trust between you and the referring physicians. Why? Because they show that you are honest.

4) Ask others

I do it all the time; everyone needs a second opinion - or help. It is the power of “collective wisdom” that has led to such rapid developments in science. Why not use it more often when it comes to ultrasound. Here is a personal example: Do you know what the following off-axis subcostal view shows?

Polycystic kidney syndrome

Polycystic kidney syndrome

I didn’t know several years ago until I took the study to a colleague from radiology who explained to me all the features of Polycystic Syndrome. That’s exactly what this patient had. The lesson here: Ask others and your competence will increase, your reports will get better, and colleagues will have more trust in you.

I know that it is often difficult to find a mentor. But even if no one is there to help - you still have the Internet where you can find many forums to post your cases, questions and more.

5) Follow up on your patients

Have you experienced the following situation? You see a patient with strange pathology and you are not certain what is. You describe it in your report and the patient leaves the lab – and that’s it. You did your job, and after a few hours or maybe a day or two you have completely forgotten about the patient.

One of the biggest mistakes I see in trainees is that they don’t follow up on their patients. Many are not interested to find out what became out of them, or what the abnormality they saw actually was. A tumor? Vegetation? Or maybe a thrombus? Did the procedure go well? What was found on autopsy? What was the autopsy result?

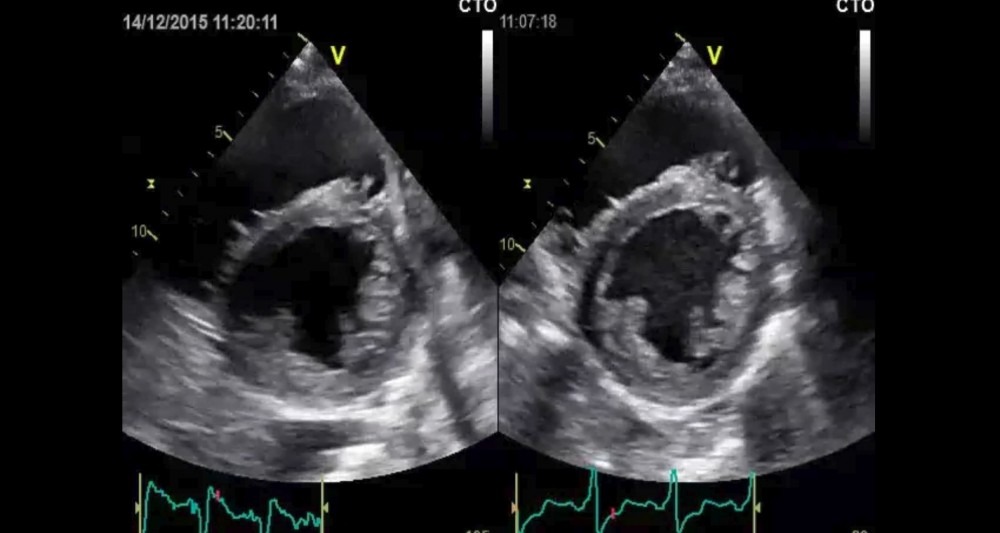

Sometimes it would be quite easy to get the answer. Call the patient in for a repeat study. Here is an example of a patient who had severe mitral regurgitation with severe pulmonary hypertension and I was wondering how the” LVF truly was before surgery (left).

After MV repair (right) the pulmonary pressure dropped significantly (no “D shaped ventricle” anymore) but one can tell that LVF has deteriorated. This demonstrates that we probably were not aware that the left ventricular dysfunction was already present before surgery. Reduced afterload and the D shaped ventricle prevented us from detecting the problem before the operation.

Echo before and after MV repair

Echo before and after MV repair

Here is my recommendation: Make a list of patients that you need to follow-up on. Reserve a few hours at the end of the week to go through the list. Research the outcomes of your patients. Act like a detective and close the “loop of learning”.

What we learned:

What do all these tips have in common? All of them require a high level of engagement with the patient during and after the act of performing ultrasound. They all require curiosity and passion for your job. But isn’t this the reason we choose our profession in the first place?